Scientists think they know what animal carries mpox. It’s not a monkey

It’s a question that has puzzled scientists since mpox was first discovered in the 1950s: which animal carries the virus and helps it spread?

A group of researchers finally have an answer. They believe they have identified the animal that can carry the disease without being sickened by it – and it’s not a monkey, it’s a squirrel.

The fire-footed rope squirrel, a forest-dwelling rodent commonly hunted and eaten by both humans and mammals in West and Central Africa, appears to serve as a reservoir for the virus, much like bats with Ebola or rats with the plague.

For years, experts have suspected small rodents were spreading the virus formerly known as monkeypox – a name given to the disease after it was first discovered in a group of lab monkeys.

But it was only after a chance discovery in 2023 that they could identify a culprit.

Researchers from the Helmholtz Institute were studying a group of mangabey monkeys in the forests of the Ivory Coast’s Tai National Park when they noticed something unusual.

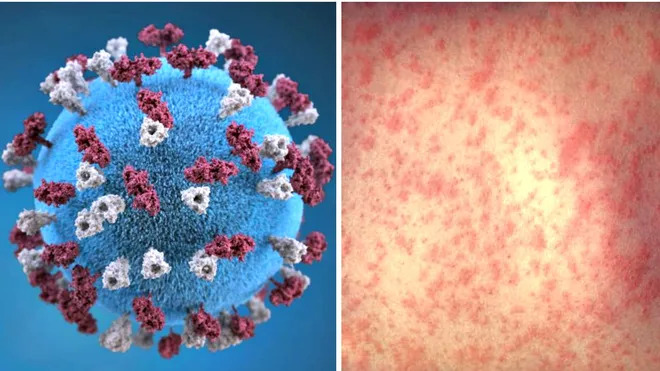

A baby monkey had developed red, pus-filled skin lesions characteristic of mpox on its forehead, chest, and legs. The blisters spread rapidly and the monkey died two days later. Within two months, 80 of the monkeys had been infected, and four others had died.

Having monitored these monkeys since 2001, the outbreak provided a rare opportunity to trace the point of infection. The researchers had decades of samples and data to analyse, as well as cameras set up in different parts of the jungle to observe the monkeys’ behaviour.

Soon, they discovered the infant who had first attracted attention wasn’t the source of the outbreak after all. Instead, it was his mother, Bako, an elderly mangabey who had recently eaten part of a fire-footed rope squirrel.

An asymptomatic mpox infection was quickly confirmed by samples from her urine and faeces.

Then the scientists found the squirrel’s carcass less than two miles from the monkeys’ territory, and it was teeming with a virus identical to the one infecting the mangabeys.

DNA sequencing confirmed Bako had been directly infected by the squirrel before transmitting the virus to the rest of her troop.

“It’s unbelievable how well things fit together,” Fabian Leendertz, leader of the work and founding director of the Helmholtz Institute, told Nature.

“This represents an exceptionally rare case of direct detection of an interspecies transmission event [and] our findings strongly suggest rope squirrels were the source of the [mpox] outbreak in mangabeys,” the researchers say in the paper, which has not yet been peer-reviewed.

Dr Leandre Murhula Masirka, who discovered a new, more dangerous strain of mpox known as clade 1b in the Democratic Republic of Congo, thinks it’s very likely that the virus originated in rope squirrels.

“Historically, nearly all the outbreaks of clade 1 mpox in Africa have been in areas where people commonly eat rope squirrels,” he told The Telegraph.

“The rope squirrels that I have tested always have antibodies for mpox, and I think they are the most probable species to be the reservoir of the disease,” he added.

Other experts are more circumspect, however, arguing that though the squirrels are certainly capable of carrying and transmitting mpox, there is not enough evidence to say definitively that the squirrels are the virus’s natural reservoir.

“The identification of the fire-footed rope squirrel as a potential reservoir host for the mpox virus is a significant advancement in understanding the virus’s transmission dynamics,” said Dr Krutika Kuppalli, associate professor in the division of infectious diseases at the University of Texas Southwestern.

“It will be important however to continue conducting research to confirm these results and to identify additional potential reservoir species such as rodents, primates, or other small mammals,” she added.